By JOSHUA MANDEL, MD, DAN GOTTLIEB, MPA, and KENNETH D. MANDL, MD, MPH

June 1, 2023

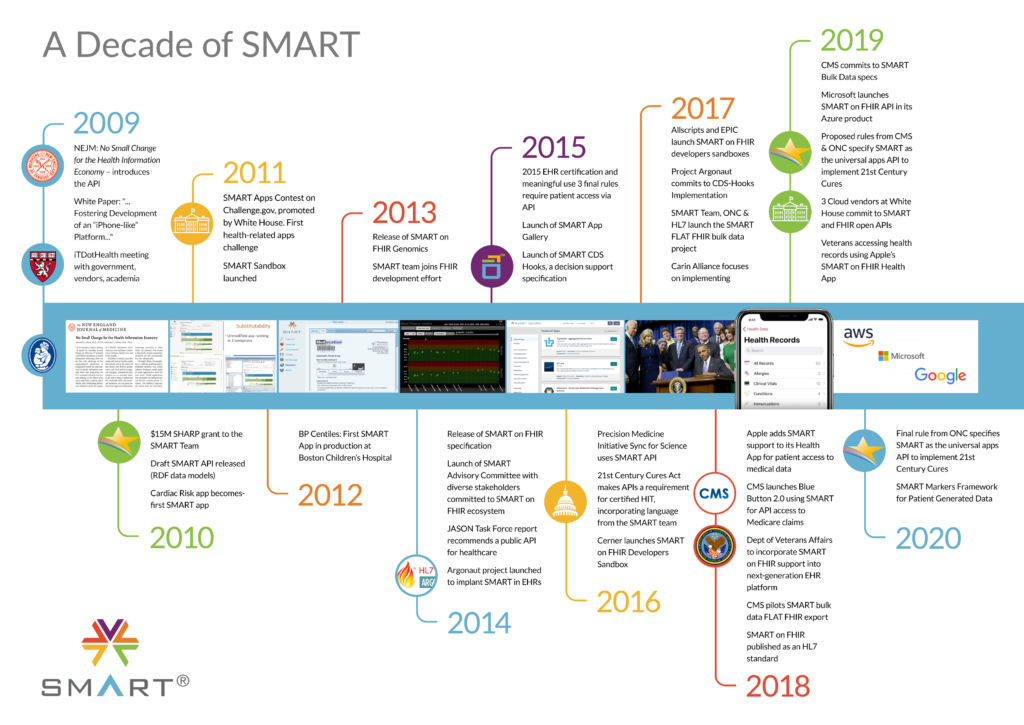

Thank you for the opportunity to comment on the HTI-1 proposed rule! We understand that it takes time to see the effects of recent changes, as many of the effects of previous regulations are just now making their way into practice. It’s important to learn from experience and focus new regulations on demonstrated approaches. Given the design and demonstrated value of SMART on FHIR and SMART/HL7 Bulk FHIR Access API, we urge strong consideration of their use, or at least testing, in addressing use cases. The bandwidth of Health IT developers to reliably surface multiple APIs addressing minimally different use cases (e.g., quality metric reporting, eCR) may be better spent on ensuring performant SMART APIs with reliably mapped USCDI elements.

In the current landscape, we see many reasons for encouragement based on the roll-out of API access in 2023, especially for single-patient use cases (clinician and patient-facing apps). However, we recognize ongoing challenges that API users are experiencing with FHIR API performance and workflow for high-value population-level use cases at scale. More clarity on expectations from ONC and CMS is needed to ensure consistent and performant population-level APIs as are meaningful metrics.

USCDI Definitions and Expansions

We strongly support USCDI as a common basis of exchange. However, there are challenges in a one-size-fits-all model of “the core data set” — some elements are a stretch for EHRs, and other elements (such as, concepts common to payors systems) aren’t addressed deeply enough. We’ve also seen significant standards-development challenges around vague or ambiguous elements in USCDI. This leads to churn in the standards process, widespread optionality in the standard profiles, and, due to wide variation in formats, limited capabilities that may be unsuited for the use cases of the submitters who advocated for the inclusion of these elements in USCDI.

Our Recommendations

- When adding elements to USCDI, ONC should:

- Explain a set of intended use cases

- Provide details about how and how frequently these data are being used to meet the intended use cases in real-world systems today, which will help the standardization effort to build on real-world experience and achieve ONC’s desired outcomes.

- Within USCDI, ONC in its coordination role can pre-group data subsets, for example tagging them as related to demographics, clinical, financial / payment / insurance, or imaging.These tagged subsets could then be pulled in by other programs beyond the EHR, such as CMS regulation of the APIs and data responsibilities of payors.

Decision Support Interventions

This is a significant and expanding area of great clinical import. Many predictive capabilities are expanding rapidly. Transparency and mitigation of bias are imperative. However, we believe that regulating a specific set of data and model attributes is premature, as there is not yet consensus on the set or structure of such attributes. Many techniques are evolving in parallel, and even a functional requirement that’s opinionated about (numerous!) specific data classes risks producing unintended consequences, such as information overload in the clinical UX and incomplete and unhelpful “box checking” data.

Targeting new regulations at EHRs here may also have unintended consequences. EHRs are integration points for diverse decision support, and choices about how to assess and manage risk are a core responsibility of the clinical providers deploying decision support. Imposing requirements on EHR vendors may lead to proliferation of decision support that route around the EHR rather than through it.

Our Recommendations

- Add first-class support for CDS Hooks as an alternative to InfoButton

- Do not regulate a specific set of attribute unless/until such attributes are successfully incorporated into some real-world deployments

- Do not regulate “data review” UX requirements unless/until this is demonstrated to work in practice

- Emphasize the importance of providing model cards and similar data to health systems at the time of selecting/configuring decision support, rather than overloading clinician-facing UX at runtime.

- Emphasize that responsibility for risk assessment and mitigation should be shared with DSI providers, rather than falling onto EHRs.

Public Health: Electronic Case Reporting and Surveillance

There is a substantial opportunity to empower Public Health with data from the care delivery system in far more robust ways than have been accomplished in the past. The most promising approach will be to ensure that Public Health does not rely on one-off solutions, even ones specified in rules and regulations, but rather derives data from common data infrastructures used by CMS and other entities.

Proposed case reporting and surveillance standards are complex for EHRs, with dynamic behavior required from every EHR, intricate temporal logic, and value sets that change over time without standard update protocols. Proposed case reporting standards are also brittle, with significant effort to support public-health-specific APIs, requirements that still vary by jurisdiction, and limited ability to predict future needs.

Our Recommendations

- Focus on enabling public health use cases through existing SMART on FHIR and SMART/HL7 Bulk FHIR Access APIs rather than one-off public health-specific protocols

- Leverage SMART on FHIR backend services and apps that:

- Can be authored or sponsored by public health

- Can manage alerting logic nimbly without per-EHR repeated work

- Consume existing FHIR APIs and trigger from US Core data

- Expand existing APIs to ensure support for cross-patient queries, such as:

- GET /Encounter sorted by time, code, category

- GET /Observation sorted by time, code, category

- GET /Condition sorted by time, code, category

- Invest in FHIR Subscriptions as a performance optimization, such as “US Core Event Feed” as a Subscription Topic, which supports filtering by resource type, patient, code, and category

- Expand required parameter support on the FHIR bulk data API to:

- Mandate support for the “_since” parameter, allowing apps to request only data modified after a specified date

- Mandate support for “_typeFilter”, specifically to allow filtering of:

- Patient resources by demographic information

- Observations, Conditions, and other US Core resources by category (where applicable) and code (where applicable).

EHR Reporting Program

We appreciated the chance to participate in prior rounds of measure planning and applaud ONC’s introduction of specific measures. However, we are concerned about the complexity of the proposed measures, with multiple numerators, denominators, and stratifications, and unclear exactly what reporting data are being proposed. We are also concerned that many measures imply the collection of new types of data, such as app categories and intended audiences.

We are further concerned that some metrics propose to segregate by an unreliable concept of “two different endpoint types: patient-facing and non-patient-facing.” FHIR endpoints can serve multiple and broad audiences and need not have a “type” like “patient endpoint” or “provider endpoint”.

Our Recommendations

- Start with a smaller reporting set and expand over time

- Focus on data elements already known/available

- Assess usage based on user types (e.g., patient vs provider — these are tracked and consistent), not “endpoint types” (which are not distinct in all deployments).

- For bulk data requests, include at least one metric to track the real-world performance of implementations

- Key metrics:

- Consumer access (SMART on FHIR)

- Count of distinct apps connected

- Count of app connections per patient

- Count of portal sessions per patient

- Clinician access (SMART on FHIR)

- Count of distinct apps connected

- FHIR Bulk Data API

- Count of export requests

- Export time per resource (average)

- Group size for successful exports (average)

- Consumer access (SMART on FHIR)

FHIR Endpoint for Service Base URLs

We strongly support the ONC’s addition of specific metadata requirements for endpoint URL lists to help patients identify the correct endpoints for their healthcare providers. We are concerned about the specificity of the guidance around FHIR resources and data elements in the regulations and believe that introducing more detailed functional requirements instead would encourage the industry to refine and align on technical data profiles.

Our Recommendations

- Enhance the existing functional requirements by mandating that published endpoint lists support: physical locations, organizational hierarchies, patient-facing brand names, and institution logos.

- Encourage industry evaluation of detailed FHIR implementation guides to meet these functional requirements. A starting point is the Argonaut Project’s 2022 “SMART Patient Access Brands” profiles (available at https://build.fhir.org/ig/HL7/smart-app-launch/branches/pab/brands.html).

Standards Updates: SMART v2

We have been encouraged to see the breadth of adoption and are pleased to see the enumeration of SMART capabilities and clear rationale in HTI-1 — such considerations help justify industry investments. We agree with the features that HTI-1 proposes to require.

There has been ongoing confusion about consumer ability to connect browser-based apps persistently, without the need to re-authenticate. Previous ONC regulations guaranteed this ability for some apps but not others, drawing distinctions by client type (confidential vs public, or native vs browser-based). Previous ONC regulations also do not require support for Cross-Origin Resource Sharing, leading to a situation where some server configurations prevent browser-based apps from receiving an access token. SMART 2 introduced support for PKCE to reliably bind token issuance to a client’s authorization request, mitigating previous concerns. However, the HTI-1 proposal stil does not ensure long-term access for “public clients,” even though “public clients” can offer better data segregation than “confidential clients” by avoiding the need for consumer data to transit through a developer’s backend server. Such restrictions impose unnecessary risk by encouraging app developers to use a backend server and limit patient choice by artificially limiting the capabilities of browser-based local apps.

Our Recommendations

- Adopt the current release — i.e., SMART 2.1 (not 2.0), which includes:

- Improved FHIR Context management

- App State capability

- Mandate support for client-side browser-based apps:

- Mandate that consumers can approve “offline_access” scope for any registered app, not just confidential or native clients

- Mandate that servers “support purely browser-based apps” per https://hl7.org/fhir/smart-app-launch/app-launch.html#considerations-for-cross-origin-resource-sharing-cors-support

Information Blocking: TEFCA Condition for “Manner” exception

Organizations today have the right to negotiate the manner of access, however, HTI-1 notes that “it is reasonable and necessary for actors who have chosen to become part of the TEFCA ecosystem to prioritize use of these mechanisms”. We believe that artificially limiting this right for organizations that participate in TEFCA may have unintended consequences. TEFCA has not yet launched, and it is unknown what full-scale challenges may emerge. Some organizations may participate in TEFCA out of necessity, driven by certain use cases, but may not be well served by TEFCA for all use cases.

For single-patient use cases, there may be a significant delay before TEFCA’s draft FHIR roadmap is widely implemented. In the meantime, organizations should be able to negotiate for the manner of access that suits their requirements, including access to a certified EHR’s SMART on FHIR patient API endpoints. For population-level use cases, TEFCA may not offer any pragmatic alternative to bulk FHIR export, even if TEFCA supports access to all of the data elements and patients associated with a bulk request. Organizations should be able to negotiate for the manner of access that suits their requirements, including access to a certified EHR’s SMART on FHIR Population API endpoints.

Our Recommendations

- Do not introduce a TEFCA Condition for the information blocking “Manner” exception

- Instead, monitor TEFCA deployments closely with an eye to utility, completeness, timeliness, ease of access, security, privacy, transparency, and consumer participation. Base decisions on real-world experience.

Patient Right To Request a Restriction (proposed new criterion)

We strongly support individual rights, including the right to restrict disclosure of PHI. However, HTI-1’s proposal does not ensure patient rights and is very likely to lead to confusing UX, mistaken expectations, and violated trust. Consumers have the ability to request restrictions, but providers do not need to follow them, and provider technology does not offer a good way to enforce restrictions even if a provider wants to. Techniques to manage and enforce such restrictions are still an open research challenge.

Our Recommendations

- Do not introduce a non-binding requirement for requesting restrictions to disclosures at this time.

- Instead, adopt two pragmatic approaches that empower patients with controls over and insights into the use of their data:

- Controls at the source: Let patients ensure data accuracy at the source, to prevent sharing of inaccurate information. Introduce a functional requirement aligning with the HIPAA right to request corrections and amendments to erroneous information. This would:

- Ensure that patient portals and patient APIs provide patients an easy path to requesting corrections to their medical records, or to amending records in the case that providers decline to apply corrections.

- Provide a clear market signal to drive participation in standardization efforts through HL7’s patient empowerment workgroup

- Insights and controls for exchange: Let patients see who’s querying their data in TEFCA, and provide opt-out controls. Since most uses of TEFCA would fall under “treatment, payments, and operations,” TEFCA represents the largest-scale non-accountable PHI flow in history. See our perspective “The Patient Role in a Federal National-Scale Health Information Exchange” at https://www.jmir.org/2022/11/e41750 for background. ONC should prevent TEFCA from driving such “dark” traffic by providing a mechanism for patients to review:

- Who made a query for my records?

- When?

- For what purpose of use?

- Who responded to the query?

- Controls at the source: Let patients ensure data accuracy at the source, to prevent sharing of inaccurate information. Introduce a functional requirement aligning with the HIPAA right to request corrections and amendments to erroneous information. This would:

RFI Response: FHIR Subscriptions

FHIR has included preliminary support for subscriptions since R3 and has recently introduced support for “topic-based subscriptions” incorporating industry feedback to enable scalable deployment. Topic-based subscriptions are available starting with FHIR R4 based on the “Backport IG” at https://hl7.org/fhir/uv/subscriptions-backport, and are natively supported in FHIR R5.

Given ONC’s current investment in FHIR R4, we suggest that introducing topic-based subscriptions via the Backport IG is the most pragmatic and incremental way to expand capabilities of the current deployed base of FHIR implementations. Using this Backport approach, the certification program could require implementers to support a limited starter set of subscription topics, functionally defined to align with core regulatory priorities. A suggestion for initial use cases would be:

- “Patient data updates.” Allow notifications when new/updated patient data are available in association with a specific patient ID. This could be used to allow monitoring by patient-facing apps that currently have to poll at regular intervals. It could also help enable public health applications that are monitoring patient encounters in the context of a reportable condition.

- “Encounter data update.” Allow notifications when a new encounter is created or when an encounter is updated within the health system. This could be used to enable integration of public health triggering and reporting logic into a clinical system without requiring each clinical system vendor to independently implement support for detailed temporal triggering and reporting logic. This might also be the starting point for a FHIR-based encounter notifications alternative to ADT, but in our experience, it is easiest to drive adoption around new capabilities rather than reworking the mechanisms for already available capabilities.

Both of these use cases could be supported by a single “US Core Event Feed” topic, which would enable subscriptions to the resources defined in FHIR US Core with filtering available by:

- Resource Type

- Category (as applicable)

- Code (as applicable)

- Patient ID (for subscriptions at the single-patient level)

RFI Response: CDS Hooks

CDS Hooks is an HL7 standard for integrating external decision support into the clinical workflow. CDS Hooks represents a mature target for standards adoption. A suitable initial target is CDS Hooks 2.0, with mandatory support for the “patient-view” hook, mandatory support for prefetch of US Core data queries, and mandatory support for “fhirAuthorization” access tokens. With this functionality enabled, CDS Hooks can be permitted in regulations an alternative to InfoButton. Beyond this introduction, ONC should articulate use cases and desired outcomes to spur industry development and maturation of additional hook types.

RFI Response: SMART Health Cards and SMART Health Links

The SMART Health Cards (SHC) specification has been used to provide COVID-19 immunization and lab results to individuals at scale including deployments in at least 15 countries. Implementers include major EHRs, and pharmacy chains, as well as public health programs from over 24 US states. Immunization records are available as SMART Health Cards for over 225M people in the USA. By leveraging FHIR and W3C Verifiable Credentials, SMART Health Cards allows sharing of static data sets, with a focus on data that are small enough to fit in a single QR code.

Building on SHC’s format, signature scheme, and trust infrastructure, the SMART Health Links specification allows for more advanced usage including larger data sets (e.g., a full immunization history or patient summary) as well as dynamic data sets (e.g., an immunization history that can be augmented when a patients receives vaccine doses). The SHL specification underwent an initial round of design, prototyping, and feedback through the Argonaut standards accelerator in 2022. Early industry adoption of SHL in 2023 has focused on immunizations and health insurance coverage details, with additional prototypes demonstrating a workflow for sharing International Patient Summary documents.

We believe ONC can foster broader adoption of SHC and SHL by sponsoring programs to identify and address unmet needs in consumer mediated data exchange. In particular, SHCs demonstrate how reducing friction to health data access makes a tangible difference for patients, and SHLs enable this access pattern to be scaled to nearly any data type or use case. In the near-term, SHC and SHL provide a common pattern for sharing use-case-specific data bundles, expanding the reach of FHIR implementation guides for sharing with minimal coordination across organizations. Over time, we see a path for this technology to support more interactive sharing paradigms that could address some of the high-frequency, high-friction touch points that people have with healthcare. This could include prompted sharing (e.g., before a clinical visit, patients might receive an information sharing request that they can review and respond to using a personal health app or wallet) as well as assisted form-filling (e.g., when presented with a blank clipboard asking for clinical information, a personal health app could pre-fill many items and, when desired, could attach verifiable provenance to the submission).

RFI Response: Industry-Led Innovation Activities

Even as API access to clinical data has become routine in practice, API access to imaging data has remained challenge. This year the Argonaut Project has organized development and testing of a specification for SMART app access to Imaging data, building on the SMART on FHIR API capabilities of Certified EHR Technology. The Argonaut design leverages existing EHR app-registration and app-approval workflows, augmenting the available data from an EHR’s “clinical server” with an additional set of imaging data from an imaging endpoint. The imaging endpoint hosts a narrow subset of FHIR and DICOMweb functionality, authorized using SMART on FHIR token introspection to allow SMART apps to list the studies available for a patient and retrieve user-selected studies. We believe this architecture offers a promising and scalable approach to enhance patient and provider access to imaging studies alongside clinical data. Such access would facilitate diverse use cases for providers and patients including:

- For Providers

- Support analysis w/ preferred tools, such as speciality-specific viewers, image-driven severity scoring, or image-driven risk calculations

- Streamline consultation workflows

- For Patients

- Enable access, compilation of full data

- Ensure data are available to specialists

- Facilitate second opinions and

- Streamline data donations for research

ONC could identify opportunities to support Argonaut Imaging and functionality that expands on the API capabilities of Certified EHR Technology. Over time, projects like Argonaut Imaging Access can serve as a model for widespread application access to a growing swath of Electronic Health Information.

Sincerely,

The SMART Health IT Team

You must be logged in to post a comment.